These are all license families, but they differ significantly, even though their names might seem similar.

Common Misconceptions.

First and foremost, many proprietary software vendors mislead users by presenting the license as if it were simply a price.

The license is a legal binding contract, not a price.

In some cases (though increasingly rare) licenses require, as a condition for using the software (i.e., executing it), the payment of a fee. However, this requirement is merely a consequence of certain license terms, not the core purpose.

Second, software provided without any license terms (often referred to as “public domain” software) grants users unlimited rights by default, not restricted ones. As a result, you are entitled to:

- Copy the software

- Run it on any machine of your choosing

- Une it for any purpose

- Run it for an unlimited number of concurrent users

- Process any amount of data with it

- sell copies of it

- Attribute authorship to yourself

- Rename it

- Publish it under a proprietary license

- Modify it

- Reverse-engineer it

- Combine it with other software (provided their licenses permit it)

- Rent it

- and more…

Therefore, it is essential to recognize that if you encounter software without any license terms, it is effectively in the public domain. This means your rights regarding its use are unrestricted, and you may engage in activities that could otherwise be considered intellectual property (IP) infringement.

The purpose of a license

is to limit your freedoms,

not to grant them.

Third, there is a common misconception that “the license applies to the copy I purchased.”

This is incorrect. A genuine license applies to the software itself—not just a specific binary (compiled) version. While some highly restrictive licenses, such as End User License Agreements (EULAs), may limit your rights to a single binary copy, this is not the standard or intended practice. A license, as a legal contract, governs the software in its source-code form, not just a single compiled executable. The widespread practice of proprietary software vendors distributing only binary versions has distorted the public’s understanding of what a software license truly entails. Historically, software was distributed in source-code format, but the proprietary software industry shifted this norm by providing compiled binaries instead.

This shift also restricts your choice of platform: if you receive a binary compiled for a Motorola CPU, you cannot run it on ARM or Power architectures. A 32-bit binary won’t function as a 64-bit application, and software compiled for Sun Solaris won’t run natively on BSD Unix—or vice versa.

Access to the source code in a human-readable format grants you the freedom to compile the software for your preferred target platform. It ensures compatibility not only with current systems but also with future operating system releases, platforms that don’t yet exist, and even hardware that wasn’t available when the software was originally written.

Therefore, a proper license (one that applies to the source code) safeguards your long-term right to use the software.

As we are committed to deliver

sustainable software

for a sustainable world,

this is the right choice.

Freeware.

In the context of “Freeware,” the term “free” refers to “gratis,” as in “free beer.”

Freeware is software distributed in binary format at no cost. Typically, proprietary software vendors offer such copies to create dependency on the software, encouraging users to eventually purchase paid versions. This strategy mirrors the tactics of drug dealers who distribute free samples in seedy alleys: hook new users and turn them into captive customers. This practice is a form of vendor lock-in.

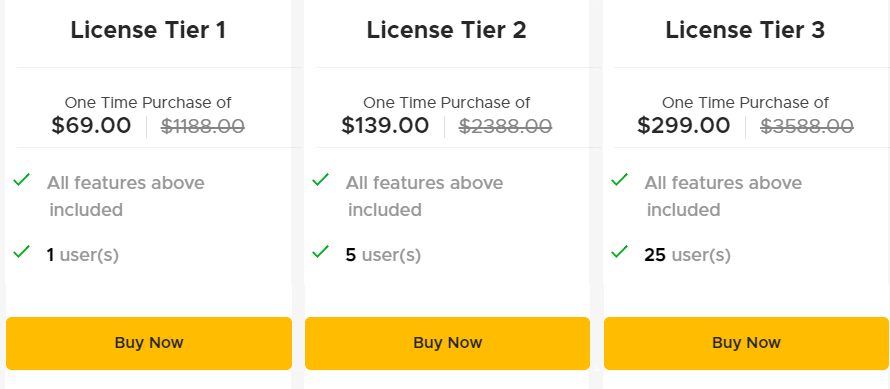

How do vendors compel users to purchase a license?

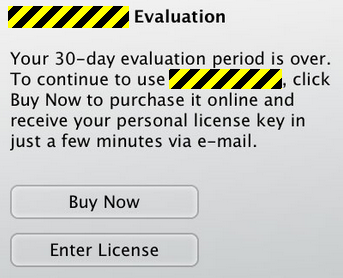

- One common method is through time-limited usage: the software (often called Trialware) ceases to function after a set period (usually 30 days) unless a license is purchased to unlock it.

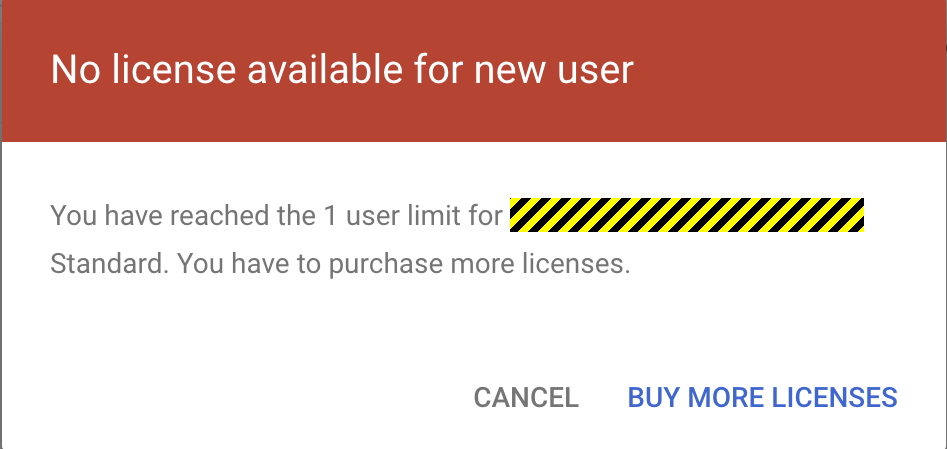

- Another approach is through usage restrictions: the software (often referred to as Freemium) operates only with a limited amount of data, users, sessions, or projects. To exceed these limits, users must purchase a license.

- Functionality limitations: The software (known as Crippleware) permits full usage but restricts critical actions—such as saving, storing, or exporting results—or locks “advanced” features behind a paywall, requiring a paid license to unlock them.

- …

This approach is also common in gaming, where the first few levels are free, but further progress requires payment, whether through money, watching ads (Adware), mentoring new users, or other means. Increasingly, the “payment” involves surrendering your personal data: browsing habits, user profiles, purchase history, location, and more. This data-driven model was a cornerstone of Google’s early revenue strategy, which is why the company heavily promotes its “free” browser, Chrome.

This practice is precisely what the famous saying addresses:

However, this isn’t always the case, as we’ll explore later under the “FreeSoftware” section.

This strategy is far from new. There are numerous historical examples of such practices. For instance, AT&T distributed free (gratis) licenses for its Unix System-V operating system to universities. The goal was to familiarize computer science students with the OS, ensuring they would later advocate for purchasing paid versions in their future workplaces.

Similarly, Sun Microsystems provided “free” (gratis) licenses for its Sun Solaris operating system to universities. “Education” editions of software, discounted versions, and free evaluation periods are all variations of the same marketing tactic (the one that mirrors the strategies of drug dealers): create dependency by offering a taste for free.

A freeware, by definition, must be avoided, not even tried. It is a trap.

FreeSoftware.

Freeware, by definition,

should be avoided entirely.

Even for trial purposes.

It is designed as a trap.

FreeSoftware stands in stark contrast to Freeware. According to the Free Software Foundation, FreeSoftware refers to software (specifically, its source code) distributed under a license that guarantees users the

Four essential freedoms

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose

- The freedom to study how the program works and modify it to suit your needs.

- The freedom to redistribute copies to help others.

- The freedom to distribute modified versions to others.

These freedoms inherently require that the software is provided in source-code format.

Misconception: Some might mistakenly believe that FreeSoftware cannot be sold. This is entirely false. FreeSoftware can be sold, and there are many real-world examples, such as the Red Hat distribution and SUSE Enterprise Edition. In FreeSoftware, the term “free” refers to freedom of unrestricted use, not to price.

For more insights on the Economic Model of FreeSoftware, you can refer to my conference (available in French).

In summary, FreeSoftware can indeed be sold. For example, a customer may commission specific developments such as new language support, protocol integration, format compatibility, GUI enhancements, or security features. Companies like SES-Astra, which rely on the Linux kernel for their satellite platforms, have paid for custom additions like Selective Acknowledgement, Large Window Size options in the TCP stack, or IPv6 support. Yes, these developments were paid for.

However, the pricing of the next copy of FreeSoftware follows fundamental free-market principles:

- Free prices

- Limited by competition

The cost of the next copy of FreeSoftware is essentially the cost of the copy (nearly zero) plus a margin, which competition keeps limited. Given the vast number of sources available for FreeSoftware, comparable to the number of websites on the internet, this margin is negligible, often rounding to zero.

The natural, fair price

of a single software copy license

is zero.

This isn’t specific to FreeSoftware. The natural price of any single software license, under fair market conditions, is close to zero. Proprietary software vendors maintain artificially high prices by avoiding competition, practices that are unfair and often illegal under antitrust and anti-competitive laws.

If some proprietary software companies have amassed shocking wealth, it’s not due to the value they add to society, but rather through illegal commercial practices that violate free-market principles.

The proof lies in the success of FreeSoftware. High-quality, state-of-the-art software like the Linux kernel (running on over 90% of CPUs worldwide), Apache, NGINX (powering most of the world’s websites), Chromium (the foundation of Google Chrome and Microsoft Edge), VLC (the most widely used video player), PostgreSQL (a professional-grade RDBMS), LibreOffice (a fully standard-compliant office suite) and hundred of thousands others FreeSoftwares demonstrate that

excellence doesn’t require

proprietary software restrictions

With FreeSoftware, the cost of a copy is effectively almost zero, and you are not the product.

With FreeSoftware, as you have access to the source-code, and freedom to amend it,

- If the software spies on you, you can remove the spying functionality.

- If usage is restricted (by user count, time, data limits, or disabled features), you can fix it.

- If features are missing and only available in expensive proprietary versions, you can add them yourself.

A real-world example of the difference between a proprietary license vers and a FreeSoftware version: OSMAnd.

If downloaded from F-Droid, you get the full FreeSoftware version, unlimited, free of charge, ad-free, and with access to the source code.

If downloaded from Google Play, it’s the restricted proprietary license version: it is limited to 4 countries, full of ads, unless you purchase a paid version.

The choice is up to you…

Free Software.

What is “free software” ?

The term “free software” is ambiguous:

- It may incorrectly refer to “Freeware” (software available at no cost, or “gratis”, but without any access to the source-code).

- Alternatively, it may refer to “FreeSoftware”, a totally different concept.

To avoid confusion, especially since “free software” is often misunderstood as “gratis software” (like Freeware), it’s best to use the term “FreeSoftware” (in one word and with capitals) specifically to describe software that respects the four essential freedoms defined by the Free Software Foundation. The capitalization helps distinguish it from the generic “free software” (which can imply “gratis”).

free software

≢

FreeSoftware

It is not equivalent. In fact, it is quite the opposite.